Yonsei Memory Project is proud to present new essays in a series called “Valley Writers Respond.” In early May, 2020, Yonsei Memory Project invited writers based in California’s San Joaquin Valley to reflect on the current moment, utilizing a single word as a prompt for writing. “Valley Writers Respond” was inspired by a strong desire to do something, to help tend to each other, to create understanding even through difficulty as we all find our ways through a pandemic. YMP has never shied away from deep truth-telling, and now, while so many are in duress, we turn to art and artists to hold space for us to process.

In “Valley Writers Respond” three Valley writers share their wisdom in short original essays. The project includes essays by Samina Najmi, Will Freeney, and Steven Church. Will Freeney, a writer, MFA candidate, and former Storytelling for Change Fellow, was invited to reflect on the word, “breathing.” Here is Will Freeney’s offering.

Breathing

by Will freeney

May 26, 2020

You can gaze out the window,

Get madder and madder,

Throw your hands in the air,

Say what does it matter.

But it don’t do no good

To get angry, so help me I know.

—John Prine, “Chain of Sorrow”

The Davis Sutter Hospital ER on a Sunday morning resembled a ghost town. It was just me and my ride there, plus one doctor and one nurse. It took a lot to get me there, though. Not a lot of money (just a cab ride), not a lot of time (just a few miles). Just a whole lot of irrefutable inadequacy. For a week, I had been unable to breathe without coughing, unable to cough without doing so convulsively, to the point of dry heaves. Without a fever or any digestive symptoms, I was still the sickest I had ever been.

After having a few x-rays taken, the doctor and nurse came out to visit me in the waiting room. With wide, sincere eyes, they looked at me in tandem.

“We have bad news and worse news,” the doctor said without a grin.

“You have pneumonia,” the nurse informed me, deadpan.

“And emphysema,” the doctor continued.

“It shows up in the x-ray, but it’s not bad yet. If you quit smoking now, you could live many more years of enjoyable life. If you don’t, it’s going to be short and unpleasant - a steep downhill ride,” he concluded.

He turned to a nearby table, plopped down a blank pad of scrips, and wrote – scrawled really – “NEVER SMOKE AGAIN!” They both looked at me with those sincere, compassionate expressions. And I was moved to determine to follow that prescription. I had never witnessed that kind of simple, pragmatic compassion in a medical environment. I would have expected them to think, if not say, “Stupid fucking smoker! That’s what you get! Don’t waste our time with your self-induced malady!” But there was none of that.

That was in 2009. With a few one-off exceptions, I have followed that prescription. And I have hiked in the Sierras; ridden my bike everywhere, everywhere I went; run a few handfuls of 5ks; swum more than ever since my triathlon training in 1999. Life has been good, and its quality has been retroactively contingent on that dynamic duo in the Davis ED. I owe them more than my insurance could ever pay. I owe them more than the Medicare (that I have lived long enough to be eligible for) could ever pay.

I owe them my ability to breathe. I am indebted to their timely diagnosis, and to the strict compassion of their prescriptive prognosis.

Then, eleven years later, along comes coronavirus with its attendant game plan, COVID-19. Back in 2009, the doctors never assigned my pneumonia any microbial perpetrator, and the emphysema was, based on my admission of over 20 years of smoking, a foregone conclusion as to cause. Now in 2020, I am over 65 and diagnosed with a suppressive respiratory disease. I belong to an at-risk population. And if I develop a severe chronic cough now, despite my at-risk status, I may or may not be able to get testing and treatment, based on the number of available test kits and beds.

Yoga instructors call it prana, martial arts instructors call it chi; breath (breathing) and life force are close enough to synonymous for most of us.

“In through the nose, out through the mouth.”

“Breathe into that discomfort. Release that tension.”

“Follow your breath: in to a count of four, out to a count of four.”

“Use your ujayi breath. Engage the back of your throat.”

I have heard all of these commands and followed them – and experienced the intended effects. You can move through and beyond pain and stiffness as you activate conscious breathing while stretching. You can increase your focus with your breath.

But without those classes and the opportunity to consider breathing rather than take it for granted, I would not have witnessed, firsthand, the benefits. Experienced the benefits of daily respirations? Of course. Been mindful of or grateful for the profound power of breathing? Nah.

Back in the halcyon era of my career as a smokestack, during my enlistment in the Army, I succumbed to the beck and call of my sergeants: “Smoke ‘em if you got ‘em!” The alternative was watching everyone else smoke. Why suffer from secondhand smoke when I could enjoy the full experience firsthand? It seemed like an avocation I was naturally suited for, and by the time I was stationed in Germany, working graveyard shifts in a commo trailer, I was up to three packs a day. I’m not sure that I would have conceded that there was a shortness of breath involved, but I felt a heaviness in my chest like someone was sitting on it. A rather heavy someone. I determined to cut back and followed through on it – returning to my previous two-pack-a-day pace and feeling good about myself and my healthy life choice. I could walk and run again without that pesky constriction.

When my subsequent wife became pregnant with my two subsequent children, she naturally, wisely, and apparently easily put down her cigarette habit, so I followed her example. There was a lapse for both of us between children, but quitting for my daughter’s gestation was the gateway to a permanent cessation for my wife and one that outlasted our marriage for me – lasting until I became romantically involved with a smoker again. It’s a common story, I am told. It’s one that I have enacted twice in this lifetime. But that vacillation is over, for this lifetime, because relapse equals death – a consequence I am not willing to bear in pursuit of a nicotine fix or an oral fixation.

And that is why I have no problem with wearing a mask and gloves or standing 6-feet away from any and all people in my environment or limiting that environment, as much as possible, to my own solo habitat.

I miss John Prine. His music and lyrics brightened my world, my life experience, my perspective on just about everything. Now, despite the best efforts and equipment available, he has succumbed to a virus. Not the insidious, ubiquitous, inexplicable vagaries of cancer; not the insular horrors of depression; but a contagious disease whose microbial agent works with a vengeance on overtime – hiding when it feels like it and sucking the capacity to breathe right out of the lungs when it is ready to wreak havoc.

I have read and watched enough now to know that COVID-19 ultimately destroys lung tissue to the point that those lungs are unusable, needing to be “replaced” in the task of respiration with a ventilator. Until this health crisis, the term ventilator didn’t sound that threatening to me, a non-medical lay person. Ventilation is a good thing, right? Freshen the air, clean out toxins in the room – good things. To be sure, the ventilator accomplishes “good things” when it can – keeping the patient alive while medical staff try to restore their health, including the ability to breathe independently.

Then, an online article on DIY ventilators left the impression of something that looked like a cross between a bedpan and a car muffler. I didn’t need that kind of discouragement. I had already read the statistics, detailing how patients assigned to a ventilator due to COVID-19 had a minority chance of survival and a likelihood of serious long-term consequences if they did survive.

So, I am not smoking ever again in this lifetime (hopefully I remember that vow in the next) in order to live a well respirated life – full of breath for talking, singing, cycling, running, walking, hiking, lovemaking ... and simple daily conscious living. It only seems like the reasonable thing to do – since I don’t want to lose my ability to breathe before I lose my life. That just doesn’t sound like a pleasant way to go. So, I think that giving up public gatherings and direct physical contact for a few months is an easy choice – a doubly easy one because I don’t want to be responsible for passing that kind of damage along to someone else without either of us being aware.

Just breathe. And chill.

Will Freeney

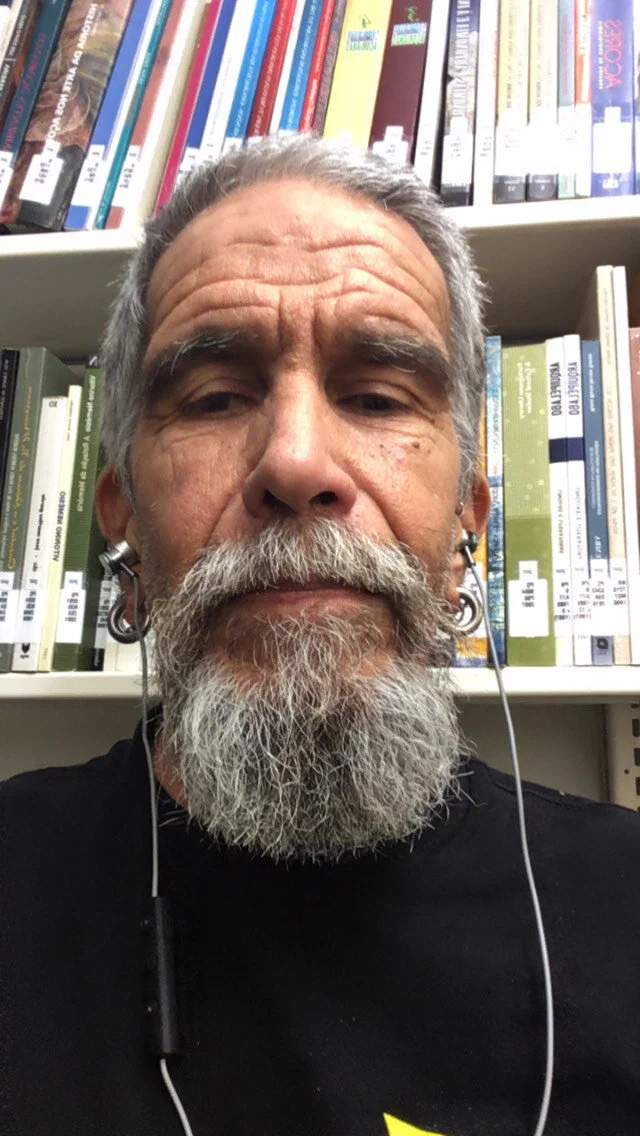

WILL FREENEY is a writer currently residing in Fresno, California, where he is pursuing an MFA in Creative Nonfiction at Fresno State University. Since his retirement from the State of California (2008), where he ended his career in civil service as a legislative analyst, he has acquired an MA in English with an emphasis in Creative Writing at Sacramento State University (2008), written for the Eureka Times-Standard (2010-2011), and written for various websites and newsletters for Strategic eMarketing (2010-present). He is currently a regular contributor to the Fresno Flyer (2017-present), a monthly alternative newspaper. His primary recreational activity is riding his bicycle around town, getting to know the community that he now calls home.